South Moravia is often associated with vineyards and agriculture, it is also home to oil deposits, a fact that is not widely known. Though not abundant, these deposits are significant due to the high quality of the raw material they provide.

Crude oil is a significant and controversial source of energy in modern times. In Czech, it is commonly referred to as “ropa.” The word is of Polish origin and translates to “pus,” as the oil found near salt springs was once viewed by people as the diseased earth’s discharge. Despite this perception, the extraction and use of the black liquid from the earth continued, earning it the moniker “black gold.”

Horse head pumps dotting rural landscapes

Located on the border with Austria and Slovakia, the Czech Republic has its own oil reserves in Southern Moravia. Stanislav Benada, a geologist and co-founder of the Museum of Petroleum Mining and Geology in Hodonín, can attest to this.

“The geological structure plays a crucial role in the presence of oil deposits, as crude oil is not found in all regions. Specific geological conditions need to be met for oil deposits to form. In southern Moravia, this involves the area along the Carpathians, stretching from the Beskids in the north to the White Carpathians and their foothills, extending into Slovakia and Austria. The Vienna Basin was the first region in southern Moravia where oil and gas were discovered and developed.”

Oil has been present on the Moravian-Slovakian border since the mid-19th century in the former Austria-Hungary. During that period, pits were dug in various locations to extract the oil, which was used in its raw form by pharmacists and craftsmen as a lubricant and impregnation agent for leather.

“For thousands of years, people have known about petroleum. In regions where it was found in abundance, like the Middle East, it was used in its natural form. However, it was not until the mid-19th century that people discovered how to distill petroleum and make various products from it. The first of these products was kerosene, which was used in lamps. The light produced by kerosene lamps was brighter and steadier than that of traditional oil lamps, and the raw material was cheaper. This led to an increase in the search for oil and the development of drilling technology to extract it.”

The Museum of Oil Mining and Geology in Hodonín offers a glimpse into the history of Moravian oil. It is housed in the former Hodonín barracks near the train station and boasts an impressive outdoor exhibition of devices. One such device is the “kozlík” or goat, a typical system used in oil extraction. Geologist Stanislav Benada explains that crude oil is typically extracted using horsehead pumps, which utilize a rod that moves up and down to push the oil to the surface.

1919 first deposit

In the early 1900s, attempts to extract oil in South Moravia began. According to Stanislav Benada, information about oil deposits came from various parts of Europe, mainly from Poland. Wealthy individuals thus started to search for the resource in the region. One of the pioneers was Julius May, who owned a sugar factory in Staré Město. Upon hearing that oil was surfacing in several locations in Bohuslavice, he enlisted a Polish company to conduct the first drilling. Although a small amount was obtained from three wells, no significant deposit was found and the site was abandoned. Nevertheless, evidence of oil extraction for lamps by locals during the Second World War has been discovered. Today, visitors can learn about the history of Moravian oil at the Museum of Oil Mining and Geology in Hodonín, which is housed in the historic building of the former Hodonín barracks near the train station and features a variety of devices in its outdoor exhibition.

The initial oil deposit, named Nesty, was found near Hodonín in 1919, and was mined until the 1980s. Further deposits were discovered during the interwar period, some of which contained both oil and natural gas. Oil production gained significant importance during World War II when the German occupiers urgently required it as a vital resource for their army. Modern rotor conveyor systems were brought in for intensive exploration.

According to the expert, after World War II, Soviet specialists took over the production and had the idea that Czechoslovakia could become self-sufficient in oil supply. Intensive prospecting took place in the 1950s with up to 40 drilling sets being used simultaneously. The deepest drilling occurred in Jablůnka near Vsetín, reaching a depth of 6506 meters. However, it was gradually discovered that the potential of the oil deposits was not as great as previously thought. In the 1960s, the investigations were scaled back.

Oil self-sufficiency of Czechoslovakia?

“There are around 50 oil deposits in Moravia, which is a significant number. However, the Czech Republic is not self-sufficient when it comes to oil production. Currently, oil production only covers around one percent of the country’s oil consumption. The productivity of each deposit varies, and production levels fluctuate, but are never particularly high,” says Benada.

The high-quality oil extracted in the region is known for its lack of sulfur, which is a negative element that needs to be removed before processing to prevent its release into the air during combustion. The expert further noted that the local oil is still highly valued because of its paraffinic properties, making it suitable for use in the production of medicines, cosmetics, and lubricants. However, the demand for these products is lower than the demand for fuel, which is why most of the oil is processed for fuel production.

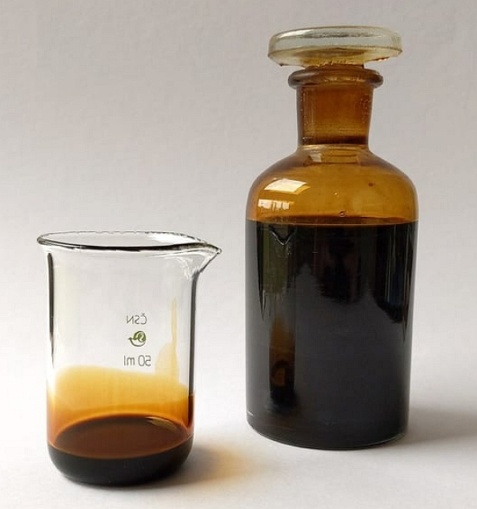

The museum in Hodonín showcases operational replicas of mining machinery and features an extensive collection of exhibits from private collectors and companies. The displays also include finished products such as petroleum, gasoline, diesel, and heating oil. Moreover, the museum provides insight into the process of how oil was formed.

According to Stanislav Benada, the formation of oil can be traced back to the decomposition of dead algae and microorganisms in the sea. After their death, their remains sank to the bottom of the sea and over time, layers of black mud and black shale were formed.

“As other sediments covered these layers, they were pushed to a depth of two kilometers below sea level. At this depth, the organic material underwent a slow transformation into carbohydrates such as methane and ethane due to the high temperatures of 90 to 100 degrees Celsius. These carbohydrates would then rise to the surface until they encountered a layer of sandstone. If the layer of sandstone was bent or broken, the carbohydrates would concentrate there and form a deposit.”

The museum in Hodonín showcases this process and displays working models of mining machines and end products such as petroleum, gasoline, diesel, and heating oil. Additionally, the museum also features hundreds of exhibits from private collectors and companies.